Baltimore on Edge — and on TV

By • May 21, 2015 0 740

If reading about the news in a newspaper allows for a certain amount of detachment, perspective and evaluation, watching news being made on television is an altogether different kind of experience.

Depending on where you are—at home, gathered with friends, in front of your iPad—news as it happens covered by local or cable television news broadcasters is almost as chaotic as the images you see live in the here-and-now, mixed with repeated imagery from the hour or minutes before, accompanied by reporters reporting from the scene and anchors anchored to the breaking news desk.

This is pretty much what happened as we watched events unfold in Baltimore in the afternoon and early evening hour. This was Monday, the sorrowful day when Freddie Gray—the young African American man who died after being arrested and held in custody by police of an apparent spinal injury—was mourned, eulogized and buried. The funeral was, according to its organizers, a solemn occasion for mourning, grieving and perhaps the beginning of healing.

Gray’s death—punctuated by marches, and demonstrations for a week, including one that ended in violence Saturday night—was another in what to many has become an unconscionable long list of African African men dying violent deaths at the hands of police. The shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, last August—in which no indictment was handed down—sparked a sea change nationwide, linking incidents in Cleveland, New York, Arizona and South Carolina, among many.

All of the incidents were different in nature but were linked by reactions to them, reactions that included demonstrations, mostly peaceful, all over the country.

The circumstances in Baltimore, where so far no investigation has been completed into the circumstances of how Gray died, were reflective of the poor neighborhoods were Gray grew up, where police and residents lived in a state of long-standing tension.

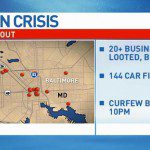

What happened after the funeral was often confusing, often violent and chaotic. It appeared from reports that police had received social media warnings that something was going to happen, and so they had gathered with their shields and helmets. After the funeral had broken up, youths from a nearby high school stormed out of the school and began running at police, pelting them with rocks, bricks and bottles. More than a dozen policemen were injured, some suffering broken bones, two of them seriously.

After that, events developed almost as if in a kind of haze. We watched as camera shots at Mondawmin Mall near Pennsylvania Avenue and North Avenue revealed first a trickle, almost casual group of young men broke windows and marched then ran into a CVS Pharmacy and begin looting, some pulling up in a motorcycle or car with tall trash bags. A police car was burned nearby. Youths continued to jump on a destroyed police car.

All of this seemed to be happening in slow motion—people would rush at a store—including a check-cashing business, a liquor store, as well as the CVS, then action would slow down for moments. Neighborhood adult men in suits tried to dissuade the looters and angry demonstrators. Then, they would head down the street to a another establishment.

For the hours after the funeral—which included an impassioned march by religious leaders going past some of the running, young men—there was no official word from the mayor’s office or the police commissioners. Governor Larry Hogan promised to send the National Guard, but only if asked.

Reporters from Washington, D.C., came to the scene in what was surely one of the more difficult assignments they had encountered. On WRC, the station was fortunate enough to have on hand Tisha Thompson, a member of its investigative team who had lived and worked in Baltimore and knew the geography and streets of the developing story.

Television, especially on a live and rolling story, is at best a jumble, a kind of mash of the immediate here-and-now and flashbacks to 20 minutes ago, where images of looters , burning cars and running, yelling tended to blend together with much confusion. Reporters appeared to have a hard time with assigning terminology and description to what they were witnessing, calling looters “demonstrators” and vice versa, but none resorted to the words used by Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, who called the looters “thugs” when she finally did speak, hours after the first events occurred. Her initial silence was much puzzled over by the press, which parsed every official word spoken, including those of the governor, who called out the Maryland National Guard, after “the mayor finally called and made the request.” Media took that word “finally” apart like a piñata, trashing it for meaning.

Reporters tried to show some sympathy—not for the looters so much—but the young people living under the circumstances that they did. “This was for justice for Freddie,” yelled one of the youths. Other observers decried the violence and looting, some remembering not only Ferguson but cities exploding in the 1960s.

One young man, interviewed by a D.C. reporter, yelled that the city had not helped the neighborhood when it needed it, that they couldn’t take it any more and that the death of Gray and the absence of information was the final straw.

Reporters and anchor folks vacillated with the frustration that they were reporting, sometimes sharing it, and the queasy potential of danger that they were a part of. But images also have a way of making the dramatic—fires, destroyed cars, looters running—seem a city-wide event, that we were witnessing a city-wide event when in actuality we were seeing repeated images interjected with live coverage. Some Baltimore residents will tell you that the event itself was “overblown” in terms of its coverage.

Nevertheless, a citywide curfew—10 p.m. to 5 a.m.—is now in effect for a week. Vandalized stores begin the tough job of clean-up and staying in business (or not). Wednesday’s Orioles games against the Chicago White Sox at Camden Yards will be closed to the public.

Watching from Washington was a nervous experience. This was not Ferguson, to be sure, but it was Baltimore—Fells Point, the Orioles, Joan Jett, H.L. Mencken, the Peabody, a true city of multi-ethnic urban neighborhoods, as one resident pointed out, the city of “The Wire” and Johnny Unitas which was so close to Washingtonians. It shook, I suspect, a certain sense of complacency here: the belief that it couldn’t happen here, when in truth, we might be one confrontation away from the same events, down the street from where many of us live.

- Storefront in Baltimore, Md. | WJLA

- Tim Riethmiller