Ringing True: The Legacy of Alexander Graham Bell

By • October 20, 2016 0 3440

“In our family, we don’t take sound for granted,” explained South Carolina mom Christy Maes in a telephone interview. The quote is also in a brief video about her son Neil, now 12, diagnosed as deaf while still an infant.

The people at the Georgetown-based Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing don’t take sound for granted either.

Founded and continuously inspired by its famous-inventor namesake, the organization has been working hard to make sure that sound — words and language, but also the sounds emanating in the course of daily life — can be heard by those diagnosed with deafness and hearing difficulties.

Working especially hard is Emilio Alonso-Mendoza, chief executive officer since 2014 of what is known, shorthand-style, as AG Bell. The seasoned leader of nonprofits will tell you that he was attracted to AG Bell by the enthusiasm and talent of the staff. But it was the organization’s mission — Advancing Listening and Spoken Language for Individuals who are Deaf and Hard of Hearing — which confronts and changes a silent world, that moved him most. Its long official name comes with a long history, tied to innovators who used their gifts to help others have an equal share of the world we all live in.

The story of AG Bell can be found partly in the story of the remarkable Alexander Graham Bell and his remarkable times, partly in the National Historic Landmark that is AG Bell’s headquarters and partly in the men and women who plan and execute its goals, chief among them Alonso-Mendoza. Equally important are the stories of the thousands of families who have dealt with the hearing difficulties and deafness of their children, such as Christy Maes and her son Neil, along with his younger sister Erin.

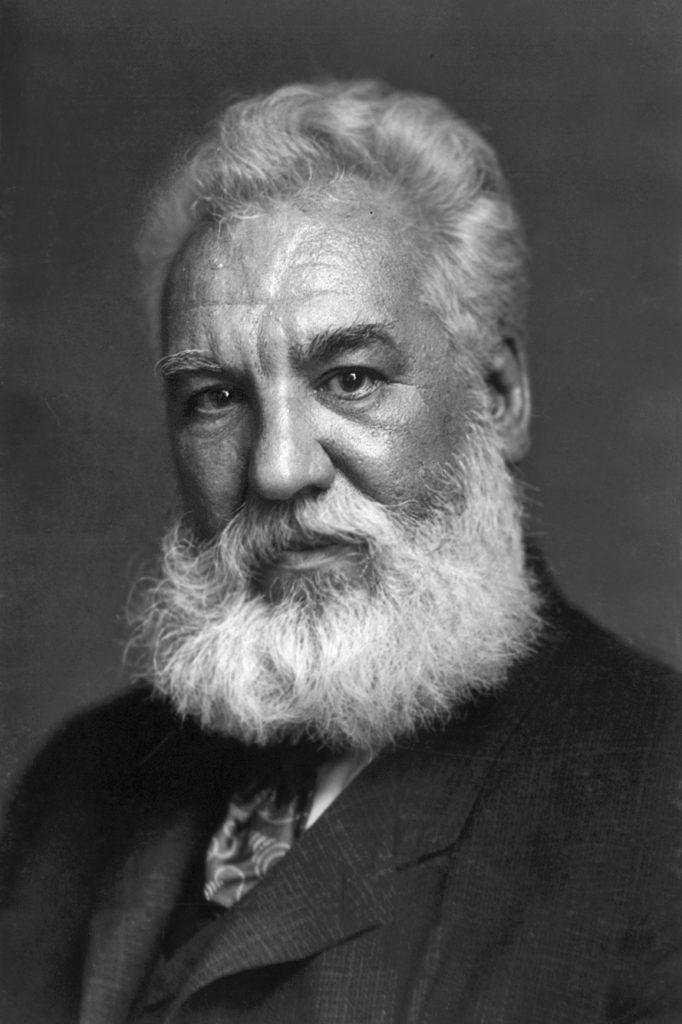

Bell was a giant of innovation in an age and a time when such men — including Thomas Alva Edison, Bell’s eccentric but far-reaching rival as an inventor — transformed the Victorian world into the modern. This was the age of the railroad and of the early development of the automobile and the airplane, signaling the transformation of transportation. There was a simultaneous revolution in communication, in which Bell played a major part — and not only for his invention of the telephone.

It turns out that Bell had a deeper view of himself and his life’s purpose. Alonso-Mendoza visited Bell’s summer home Beinn Bhreagh (“beautiful mountain” in Scottish Gaelic) in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where Bell and his wife Mabel lived part of the time and where they are buried.

“It is an amazing place. I saw the grave and the tombstone,” Alonso-Mendoza said. “It read, ‘Inventor, teacher of the deaf.’ ”

Before he became the long-bearded master of invention we know, Bell was a teacher of the deaf; his mother, Eliza, was hearing-impaired, as was his wife Mabel. His teaching was grounded in lipreading and other 19th-century methods, the fundamental idea being that speaking was the key to hearing.

Bell’s larger-scale efforts began with the establishment in 1887 of the Volta Bureau, a center for research and education on deafness, which six years later moved into the neoclassical building that remains its headquarters, 3417 Volta Place at the corner of 35th Street NW. (The name Volta came from the Volta Prize, awarded to Bell by the French government for his invention of the telephone. The original Volta Prize was given by Napoleon to Alessandro Volta, inventor of the electrical battery, whose name is the source of the terms “volt,” “voltage,” etc.)

AG Bell works with families, health care providers and educators, and its subsidiary, the AG Bell Academy for Listening and Spoken Language, offers training in auditory-verbal education, a kind of advanced certification. But the organization’s principal motivation and goal is public education.

“Part of our responsibility is to make sure that the public is aware that people who are deaf and hard of hearing can listen and talk, and to help them recognize that the children and adults we support can thrive and participate in the mainstream,” says Alonso-Mendoza.

Helen Keller was one of Bell’s protégés, and you can see her, age 13, in vintage photographs of the Volta Bureau building’s 1893 groundbreaking, along with Alexander Graham and Mabel Bell and other Bell family members. There are aspects of the 19th-century building that speak to its own time and to the special nature of Georgetown. From the rooftop, you can see a good part of historic Georgetown in something of a time-travel vista.

Alonso-Mendoza, who traces his lineage to Cuba, Spain and Venezuela, speaks in an accented, formal voice that carries well, with an emphatic style that is also full of empathy. He knows how to put public and economic focus on worthy causes, having headed the Catholic Community Foundation, the Children’s Home Society of Florida and the National Parkinson Foundation. “I was trained as a lawyer, but somehow that wasn’t enough for me,” he said. “I think I have practical, pragmatic gifts, but I wanted to do more. I want to help humanity.”

Still, there was something special about AG Bell that attracted him, which moved him.

“I tried to imagine, in the end, what this was all about. I tried to imagine what it could be like to live in a world of silence, where you would not be able to hear a symphony, where you would not hear crying, or recognize it, the normal sounds of the world, or someone singing.”

Christy Maes learned all about that when her son Neil was diagnosed, first with hearing problems, then with deafness. Technology has long provided assistance to the deaf and hearing-impaired, through hearing aids, of course, but most dramatically through the use of cochlear implants, which Neil received early on. The inventor of these electronic speech-processing devices, William F. House, is represented by a bust prominently displayed in one of the first rooms at the Volta Bureau.

“It was a process, there were other things going on initially,” said Christy. “He had the newborn hearing scan and that’s what we were faced with. But we sought out everything, and he had the implants within a day or so of his first birthday. You just do everything you have to do, and believe me it’s not easy.”

Neil, who turned 12 on July 13, came to Washington in May as one of 285 contestants in the Scripps National Spelling Bee (he was knocked out by ‘polychromatic’). Guests of AG Bell, the family worked with the organization to share the story of “their challenges and triumphs in their journey with deafness.” While Erin, 6, is hearing-impaired, Neil’s other sister, Jenna, 7, is not.

“We were shocked when we first got the diagnosis, but took it as a challenge,” said Christy. “I wanted him to thrive. And he is such a smart, good kid, anyway. He’s shy and quiet, but he dives into things. Some of it is painstaking — the give and forth, ‘Can you hear this word, or recognize this?’ — but you do it, and he was a natural. He likes German words a lot, just because they’re fun to pronounce.

“You know what happened with all of us, the whole family, we felt blessed in some ways,” she said. “That’s what not taking sound for granted means. Going through this made all of us appreciate hearing and sounds — a dog barking, the sound of rain falling or wind blowing, accents and voices. It’s funny. He turns his implant off when he hears thunder.”

She said, “I wanted him to succeed. He’s very creative. He plays the piano and the clarinet, like his grandfather, who loved Pete Fountain.

“I am so proud of him,” she said.