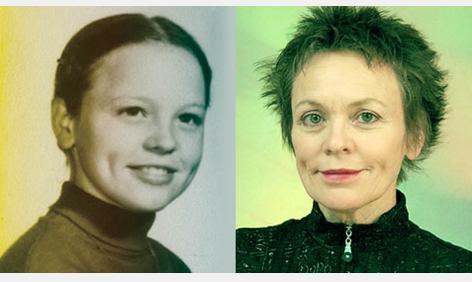

Laurie Anderson’s Magical History Tour

By • March 18, 2016 0 1305

When it comes to Laurie Anderson, the word “icon” comes to mind. In her program, “Language of the Future: Letters to Jack,” performed with cellist Rubin Kodheli at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater last weekend that word comes to mind, but I find myself resisting.

You want something more simple than her resume in the program or available online, both of which are long and informative, but not necessarily revealing. Anderson is in her sixties now and has been doing challenging, footloose creations of works of performance art, or art-art, film, music, instruments, singing-talking, with and without someone, since the 1970s. In 1981, she sort or burst into the world consciousness with a little number called “O Superman,” a hit song — yes, a hit song — which you can see performed online, and which reached number two in the British charts, which may tell you something about what was going on in British pop mentality those days. It was a chant and a song, part of a larger project called “United States” as well as “Big Science.”

These titles, incidentally, sound like novels, epic poems, a wandering poet-minstrel in search of a large subject. Anderson was married to the late iconoclast and soulmate Lou Reed. His jarring, boundary-stretching music, we recall — dum dad um, take a walk on the wild side. He died in 2013.

There is all of this, too much to take in, all at once, the many, many projects, including the affecting film “The Heart of a Dog”, about the last days of her dog in which we learn that you can teach an old dog new tricks (like learning to play the piano).

None of this is nonsense, but it is just a little too much. None of it prepares, and none of it is suggestive of what Anderson does. There is even a category for invention: the tape-bow violin. She has been doing what she does for a long time now, and one thing I can say is that she is exactly suited for our times, nonetheless. She has not seen and done everything — it’s as if there’s a lot to fill in.

Anderson makes you ramble. In “Language of the Future: Letters to Jack,” she reveals herself to be above all a story teller, a contemporary Scheherazade, who uses words, music, video, film, like a roadside witch, to beguile us into thinking of our own stories.

On a stage, she is a small presence, heard every which way, playing a violin, a version she invented herself, surrounded by tablets and electronics, alongside Kodheli, framed behind her by back projections, of snow falling unbearably wet and slow, of pictures of the Kennedy folk (hello, Pierre Salinger). She begins to talk about herself as a young girl in a Midwestern small down. The voice is seductive, warm as a heated drink, inviting even, self deprecating. She talked about the letters to Jack, which refer to Jack Kennedy — John Kennedy, a presidential candidate at the time.

“I had this confidence, self-awareness, annoying teenager type, that was me, and I wrote a letter to him, and told him I was also running for office, for student council, and if he couldn’t perhaps write back to me with some advice and pointers.” And Kennedy apparently did with one simple thing: “Find out what the people you know want. Then, promise them everything.”

Later, she wrote another letter, she said, to Jack, pointing out that she had won her election. Nothing happened for a time, and then a package came. There was a note of congratulation on her victory, and inside the package were a dozen roses. “Everybody in town knew about it and that was something special, of course, because every female in town was in love with Jack Kennedy at the time.”

Other things happened. When I was 14, she said, I was at a pool in town and watch people doing somersaults and I thought, that looked easy, and I could do that and I went off the board into the air like a bird and I missed the pool. She broke her back and nearly died and did not fully recover for a long time and spent considerable time in a hospital where nurses read books about a grey rabbit and she would wake up to their faces. “But at night, they left, and I was in a ward full of children with burn injuries, and at night, when it was dark I would hear them breathe, moan and scream. And some of them disappeared and died and for a long time I did not allow myself to remember that, about the ward at night and the screams and dying children.”

In between these forays into stories, there is the music — both disjointed and suddenly beautiful in ways hard to talk about. It is not soothing — the mix of this particular violin and other sounds and the aggressive cello are a bit other worldly, but not necessarily warm or comforting. They are meant to be listened to carefully, because there appears to be no plan, no guided composition.

There are other stories still. One about the grave of Herman Hesse in Switzerland where she left a not entirely respectful note. A longer tale was about going to a convent where she was going to be doing a workshop of some kind, and how the nuns rarely if ever spoke, and how one night, there was a gathering, which resulted in a sentence that you might never expect to hear in your own and whole life: “After the pizza was delivered, the mother superior began to speak.” It was a striking sentence.

Through it, the presentation, her voice, especially and the stories, inspired you to drift off into other stories and memories — not to stray far off, the stories and the words and the music and images were like jumping off points.

I thought of a lunch where Salinger was present among us. I thought of not reading Hesse, but Rilke, and not Gibran, either. I thought of high school, and how even now, when some of my classmates from the 1960s have found me on the Internet. I still see them with butch haircuts and pony tails. Then, I remembered a girl from a summer I spent working at a Howard Johnson on the Ohio Turnpike, who had thoughts of becoming a nun, and who wrote me a letter about how in 1960 she was going to work for Nixon — and that though we disagreed, we lived in such terribly exciting times.

Towards the dark side of the sold-out evening, Anderson brought us jarringly to 2016 with another letter, this one to Donald Trump. Her voice was electronically cloaked, sounding like one of those voices you always hear on secret procedurals: $30,000 in cash at the park and no cops, except she was talking about promises and votes.

After all of this, I find myself thinking of Anderson as a great interloper and innovator, someone who hardly sleeps and is always making us think that everything she still does feels like fresh salad, unrepeated, new ingredients all the time, living in the modern world.