America’s Choice?

By • August 1, 2016 0 958

Here in the United States, it is the Year of the Donkey and the Year of the Elephant.

Here in the United States (perhaps not so united if you listen to some politicians), we are once again in the midst of officially — formally, and often informally and loudly — nominating the candidates of the Republican and Democratic parties for the office of President of the United States.

The Republican Party has concluded its proceedings in Cleveland, once the center of a steel industry, home of the Indians, Browns and Cavaliers. The GOP nominated business mogul, developer, and television reality-show host Donald Trump to be its candidate for president at a convention marked by raucous energy and high and low drama. It did not, however, spill into violence on the streets of Cleveland, as many media pundits and other observers had predicted.

As we write this, the as-yet-unofficial Democratic Party nominee is Hillary Clinton, who brings with her a reputation and a resume seen as both impressive and, in some quarters, a cause for suspicion. Over the weekend, she introduced her running mate, Virginia Sen. Tim Kaine, and they are about to light up the birthplace of freedom, Philadelphia.

This convention, too, will have its ups and downs, its attacks on the opposition, Trump in particular, its intemperate language, its controversies. One of the key moments will no doubt be the Tuesday speech and proceedings led by former president (and potential first spouse) Bill Clinton, introducing the Mothers of the Movement, African American women who lost sons in confrontations with police officers. This is sure to be an emotionally charged night, given the recent murders of five police officers in Dallas and three in Baton Rouge, following the fatal shootings of two young black men by police in Baton Rouge and suburban St. Paul.

The 2016 conventions represent another unique event in the annals of American political history. This year’s conventions are nominating candidates who are vying not only for the presidency, but for the status of most unwanted — if not outright hated — candidate ever, a prize for which the wild-talking, unrepentant Donald Trump holds a shaky lead over the still distrusted by many Hillary Clinton.

As was most often the case in recent conventions, there was little suspense regarding who would be the nominees; whatever talk there was about contested conventions has long since dissipated with the demise of Bernie Sanders’s challenge among the Democrats and the simple — and relentlessly repeated fact — that Mr. Trump defeated no less than 16 other would-be and wannabe presidents and gathered up more votes by a Republican than ever before.

There are, for those not enamored of the two-party platter, two other choices: Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson, the former GOP governor of New Mexico, and Green Party candidate Jill Stein.

So why do we still passionately care about conventions?

Conventions are important, no matter the inelegance, the stridency, the self-evident truths and self-evident falsehoods, the ballyhoo, the displays of self-righteousness and superego über alles. No matter how well controlled or scripted, conventions still tend to be occasions when political parties reveal themselves in all their glory, warts and all. This remains in some ways the essence of the democratic spirit, if not democracy in action. Conventions are times when we see the people at the top of the tickets more or less for real, up close and personal, along with their families, friends and ambitious supporters.

Things happen at conventions, and those events echo. More than one person, confronted with the supremely recalcitrant Senator Ted Cruz being shouted down at the end of his speech for not endorsing Trump, remembered similar incidents, especially when Barry Goldwater’s supporters, feeling their right-wing oats, shouted down liberal-to-moderate GOP candidate Nelson Rockefeller in 1964.

We get to see America. In the early days of conventions, which began around 1832, the location was often Baltimore for reasons now mostly forgotten. But thereafter the events took place in New York, Chicago, St. Louis, Denver, Cincinnati, New Orleans, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Miami Beach (twice in a row for Richard Nixon) and Charlotte (for Barack Obama).

Spurred and tabulated by a series of primaries that decided the fate of the candidates, this year’s journey to the conventions was groundbreaking. Trump upset almost all traditional political practices, mores and morals, including (with the Wall and the Ban) the boundaries of political language and proposals. He ended up leading the field in terms of vote-getting, engagement via social media and free television coverage.

Assumptions were made that his convention would reflect all of that, and it did. But in terms of drama, it could not possibly match the 1968 Democratic convention, when anti-war protesters converged on Chicago and caused what some people memorably termed a police riot. Hubert Humphrey eventually gained the nomination that year, the year of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert Kennedy, a late entry into the presidential race.

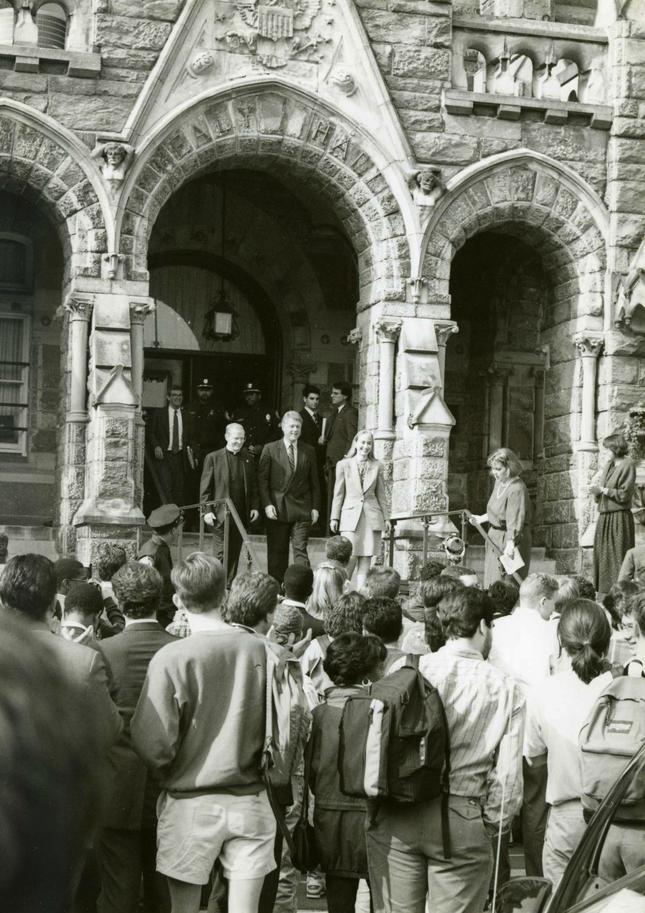

We remember conventions, or aspects of conventions. We remember Sen. Edward Kennedy, faltering as a candidate but eloquent as a speaker, taking on incumbent President Jimmy Carter. We remember Bill Clinton, not yet a presidential candidate but a keynote speaker, rambling on and on until his “and in conclusion” was met with rousing cheers of relief. We remember Barack Obama’s spellbinding keynote speech, which boosted him into national prominence. We remember the breakup of the Democratic front in 1948 with the desertion of the Dixiecrats led by Strom Thurmond, and Humphrey, then a young Minnesota firebrand, urging his party to “get out of the shadow of states’ rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.” We remember Walter Cronkite, a media figure of all things, trying to broker a deal between Ronald Reagan and incumbent Gerald Ford.

Things echo. Donald Trump’s family — the two sons, but especially the enthralling, smart Ivanka — proved to be genuine family valuables. Soon forgotten is the plagiarizing tempest in a teapot of Melania Trump’s borrowing of wifely platitudes from a Michelle Obama speech. Hard to forget, though, might be Chris Christie’s quasi, mock McCarthy-style trial of Hillary Clinton, drawing chants of “guilty” from the crowd.

Things can happen. Clint Eastwood and the empty chair in 2012; the then-youthful Clintons and Gores doing the Macarena in 1996; Ronald Reagan’s graceful speech on behalf of Bush the Elder in 1992.

Conventions are the opening salvos of what many consider the “real” campaign leading to the November elections. Elections are opportunities for branding. If Trump says he is “the law and order candidate,” what is Hillary Clinton, then, but “the adult at the table.” If Hillary Clinton is all about inclusion in a nation of diversity and immigrants, is Trump the opposite of that?

The GOP had a number of eloquent speakers who were black, who were immigrants, who were women, but a visual sweep of the gathered delegates often told a different story. Expressed in the words of Trump, the GOP appears to be about the rule of one strong leader in the service of the many, while Clinton would be about the rule of the talented many in the service of all.

The thing about conventions in this age of instant and endless communication is that the fate of candidates rests on such things as placards and chants (“lock her up” will resonate, one way or another), how candidates sound and present themselves and how their supporters behave. Conventions quite readily lead a viewer into their own cul de sacs and comfort zones.

What happens from now on out will echo. We saw another black man shot under questionable circumstances and violent shootings in Germany, reminding us of the recent tragedy in Nice. All of this instantly becomes part of the Trump vs. Clinton discourse.

Every future breath that goes out and in, a death in the Middle East, a birth in a homeless shelter, a traffic jam or a broken air conditioner here and somewhere even hotter, is the grist and stuff that’s made important by the happenings in Cleveland and Philadelphia.

One thing, though, seems missing. Writing these words, I hear Reagan and his speech, and I realize that, to some degree, it’s as partisan as any GOP (or Democratic) speech you might hear. What’s missing today is the grace and the humor he had, qualities that ought to be boon companions for any candidate on a journey to the White House.