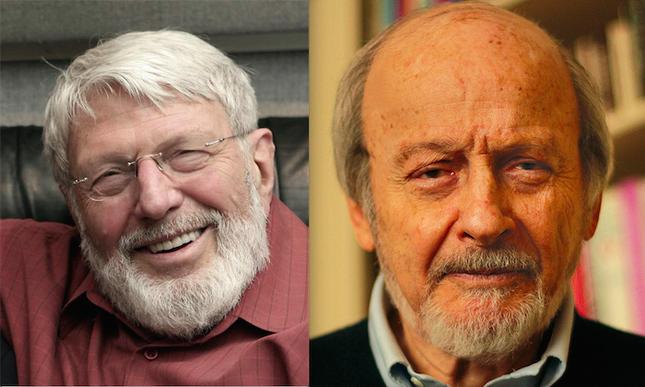

Doctorow, Bikel: ‘Larger Than Life’ Luminaries Who Enlightened Us

By • August 6, 2015 0 685

Thinking of the novelist E.L. Doctorow and the actor and musical performer Theodore Bikel, who passed away this week at the ages of 84 and 91, respectively, the phrase “larger-than-life” comes to mind, for different reasons.

Doctorow built a prize-winning literary career that was both critically acclaimed and popularly embraced, with novels that often emerged transformed as films and theater works. Bronx, N.Y.-born Doctorow lived a literary life—he wrote 12 novels, several books of short stories and a book of essays on literature.

He was a teacher or a “writer-editor-professor,” as one bio summed up. His was a life attached and garnished with honors—the National Book Critics Circle Award for his novels “Ragtime,” “Billy Bathgate” and “The March” and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal for Fiction.

This kind of literary life is the fodder for the work of critics, academics and literati, but it did not stop there. His novels not only made best books lists but also bestseller lists—and were embraced by the public, either in and of themselves or as popular works on stage and screen. His output and works were a more than modest achievement, they would put him reputation-wise in the ranks of great American novelists when that phrase was still resonant of a desired achievement among writers, although it may be less so today.

With Doctorow, there’s a feeling of a man who worked stubbornly, often inspirationally at his craft in a way that did not require celebrity or fame. But his works—the novels—were something else again. They had heft, an epic feel to them, without being of great length in terms of words and pages and even actual, physical weight. You could carry all of them in a grocery bag without risking a stroke. But their effect and result was a kind of intricately familiar waltz conducted by his creations—some of them historical figures—with the factual tropes of historical eras and actual events.

These relatively slim volumes embraced and riffed on the execution of the Rosenbergs, (“The Book of Daniel”), America’s coming of age during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt (the amazingly thick and elliptical “Ragtime”), the depression-era New York World’s Fair as a quasi-boy-coming-of-age piece (“World’s Fair”), a boy’s dangerous infatuation with gangster Dutch Schultz (“Billy Gathgate”) and Sherman’s ruinous (for the South) to the sea (“The March”), among others.

In those novels, fictional characters mixed it up with historical characters, in ways that seemed plausible, but were often fictionalized and in so doing, managed to capture the spirit of an age, a decade, a time in ways that seemed richly packed with everything the times contained. They played on what the reader knew and what he didn’t know. These novels were a form of enticement, the work of the carny barker with a spiel of bright shiny promises and elusive meanings. There was music in those novels.

“Ragtime” was the most emblematic, characteristic of Doctorow’s works. It fairly sang with a changing, robust, dramatic times without being overly dramatic or operatic. Here was the striving American family, dreaming big dreams, but unsettled by the changing times. Here were the beginnings of the movie industry. Here was Houdini, the injustices of child labor, immigrants coming ashore full of energy. Here was anarchism, a black man running afoul of already settled Irish immigrants, busting with steam and bigotry. The book seemed to contain almost every rising wave of the times covered in a style that was sharp-edged. It had the feel and emotional impact of a flowing thread made up of a series of short poems and songs. Carl Foreman turned “Ragtime” into a masterful film (with Norman Mailer in a bit part, James Cagney in his last role as a New York City Police Commissioner, Donald O’Connor as a song-and-dance man, among the large cast). “Ragtime” would later become a Broadway musical—twice—including a ground-up production from the Kennedy Center.

Theodore Bikel—who appeared frequently in Washington, D.C.—in road companies of “Fiddler on the Roof” and in plays at Theater J—may not have a “Ragtime” equivalent in his career (although “Fiddler,” even though it was originated by Zero Mostel, would certainly qualify), but his entire life and career was bigger than life.

Born in Vienna, Bikel made his first appearance as Tevye the Milkman (non-musical) in Tel Aviv. His first film was “The African Queen” (Bogart-Hepburn) in 1951, and he had an Oscar-nominated role in Stanley Kramer’s “The Defiant Ones.” He spoke nine languages and could perform in 24 languages with an accent in hundreds more. He often played Germans and Russians. He performed Tevye more than 2,000 times, probably a record for the part. He was married four times.

He created the role of Captain von Trapp in the original Broadway music production of “The Sound of Music” opposite Mary Martin. He appeared in 2005 in a highly praised production of “The Disputation” at Theater J in downtown D.C.

He described himself as a liberal Jewish activist. He appeared in the Frank Zappa film, “200 Motels.” On television, he was in “The Twilight Zone,” “Gunsmoke,” “Law and Order,” Mickey Spillane’s “Mike Hammer,” “All in the Family,”, “Columbo” and “Charlie’s Angels” and numerous versions of “Star Trek.”

Saying all that—Bikel’s CV includes a memorable role in “The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming,” and training at the Royal Academy in London, a small part in “A Streetcar Named Desire” directed by Laurence Olivier.

There was another whole career: Theodore Bikel was also a folk singer, playing the guitar, singing Jewish folk from Russia and songs and protest songs. He was co-founder of the Newport Folk Festival (with Pete Seeger, Oscar Brand, George Wein and Harold Leventhal) and took the stage in 1963 with Seeger, Joan Baez, Peter, Paul and Mary and the 21-year-old Bob Dylan.

He was a long-time civil rights activist. One could go on and on.

The life, the music, the parts, the sum of it all, the passion, the liberality of feeling and the largeness of soul made Theodore Bikel: bigger than life its own self. Ditto for Doctorow.