Ernie Banks: a Baseball Legend Who Was Real

By • February 3, 2015 0 1438

People who managed through the course of their life and after—especially after—to become legends carry with them through life and after a ,. The thing that defines them—the things they did, the records, achievements, they’re there like writings on a statue. Others might have done more or less, but what makes legends legends is a little something more, the thing that’s unforgettable, a way of walking, an attitude, something they said, the way they lived the best parts of their lives.

Ernie Banks, who died of a heart attack at 83 on Jan. 23, did a lot of things in Chicago playing for the singularly unsuccessful Chicago Cubs as their premier player—more than 500 home runs, 283 at shortstop and held a single-season shortstop homer record of 47 in one year until Alex Rodriguez came along. He had 2,583 hits, and drove in 1,636 runs, set single season records for fewest errors and best field average for a shortstop. In his last season in 1960, he won a Golden Glove Award.

He won Most Valuable Player twice — the first a first time for an MVP from a last-place team.

He got into the Baseball Hall of Fame on his first year of eligibility.

All these things are important in our data-driven-crazy world of baseball stats.

What matters more about Banks isn’t how he played the game—but how he really played the game. He coined a phrase—“It’s a beautiful day. Let’s play two”—and it was repeated every day of his life thereafter by somebody. It gets a lot of mileage after his death.

It is no small thing, that sentence. It defined him. It’s the legend part, because it describes how he played, how he embraced baseball and the gift of playing. He had a disposition, in public and on the field, that defied who he was, which was a Chicago Cub, a team that has yet to win a World Series.

Ask any athlete who isn’t as self-centered as a teenaged rock star—it’s hard to play for a team that loses a lot and to be in a city that has a team that loses a lot.

Banks made it worthwhile to be a Cub fan, to go to the ball park—he played with energy and grace. He made difficult plays look easy, and his swing was a thing of beauty.

It isn’t easy to transform a fan base despite the daily odds. You looked forward to going to Wrigley Field with more passion than any White Sox fan. You looked forward to seeing Ernie play, with optimism. In baseball, anything can happen, a fact which is its core of crazy optimism. That doesn’t mean everything will happen. Banks firmly believed it would.

Anyone who ever met him never forgot him. The Georgetowner’s publisher David Roffman, who grew up in a small town named Streator outside Chicago, was a Cub fanatic. Roffman recalled: “I was 8 years old when I first went to a Cubs game at Wrigley Field. I went with my Little League team from Streator, Illinois (Glass Bottle Blowers Assocation). Upon entering the ballpark, we were escorted to our seats by the Andy Frain Ushers. The seats were along the left field line. There, hitting fungoes into the stands so kids could have a baseball, was Ernie Banks. He became my hero and I modeled my batting stance after him throughout Little League, Pony League and High School. I would watch Cubs games on WGN all the time, and I can still hear the announcer Jack Brickhouse shout, “It’s back, back, back . . . Hey, Hey, another home run for Ernie Banks.

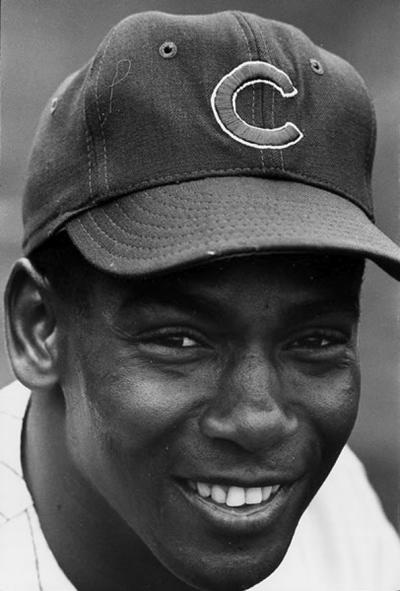

Years later, at the Crackerjack Old Timers’ All Star game at RFK Stadium, I met up with Ernie Banks (who was playing in the game along with Sandy Koufax, Joe DiMaggio and many other all time greats. I took his photograph (which hangs in my den today). It was a thrill of a lifetime for me.”

President Barack Obama, a Chicago boy himself, and his wife Michelle, a Chicago girl, called Banks “an incredible ambassador for baseball and the city of Chicago.”