3 Artful Lives Lived in Different Worlds

By • March 13, 2014 0 850

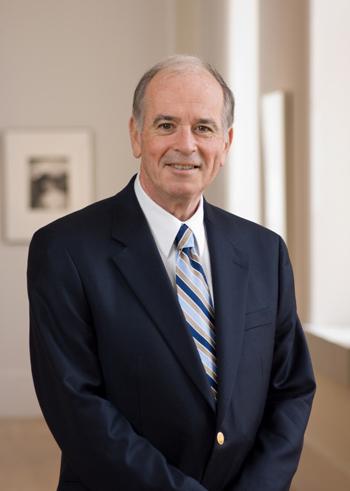

Former, Sometimes Controversial, National Portrait Gallery Director Martin Sullivan Dies

If you met Martin E. Sullivan, he would not have struck as the kind of man to excite controversy or the oft-used phrase “firestorm.”

Face to face, Sullivan, the director of the National Portrait Gallery from 2008 to 2012 who passed away at the age of 70 Feb. 25, seemed a graceful man who spoke in direct and down-to-earth terms. He came to the NPG determined to bring something of a fresh spirit to the museum in the Reynolds Center, usually associated with presidential portraits and portraits of nationally known artists and dignified achievers and historic personages. When Sullivan came, so did Elvis—in a “One Life Exhibition” as well as expansive exhibition of Elvis portraits by Al Wertheimer.

But that’s not flashed controversy. That would be the 2010 exhibition, “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture,” an expansive, ambitious and far-reaching show that meant to show the vast scope and influence of sexual differences in American art, with the works by gay artists as well as portraits of the country’s often hidden or closeted culture of sexual difference. It was as much a portrait show as it was a history show, historic for its presence as well as its subject. The show received praise in many quarters for its cultural ambition and its breadth and depth, but ignited controversies and wrath from the right and left.

Conservatives railed against the inclusion of a brief video by the late artist David Wojnarowicz, “Fire in the Belly,” which depicted briefly a crucifix covered by ants.

Conservative politicians, including Republican Speaker of the House John Boehner and members of the House Appropriations Committee, objected to the piece as did Catholic religious leaders. When Smithsonian head G. Wayne Clough ordered the piece taken from the exhibition, there was outrage from arts groups and liberals. Even so, Sullivan complied, saying he did not attention taken from the merits of the entire show or make the museum a target for cutting arts funds.

Indeed, the show was a courageous milestone for the NPG, one Sullivan could take pride in, even if it put him in a position of taking shots from the right and the left. During his career, Sullivan administered grants programs at the National Endowments for the Humanities. He was director of the New York State Museum in Albany as well as director of the Heard Museum of American Indian Art and History in Phoenix.

Alain Resnais, Last of the New Wave Directors

In the 1950s and 1960s, the world of film was overtaken by a serious interest in the works of high-minded, bravely artistic and uncommon world-wide directors, who were at the head of a movie world far removed from Hollywood.

If the name Francois Truffaut, Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, Michaelangelo Antonini, Jean Luc Godard, Louis Malle, Satjit Ray and Akiro Kurosawa ring a bell for you, then you were in your youth something of a cineaste, perhaps French, or were trying to impress your girlfriend who was studying art and living in the Village.

In those days, film—or cinema—was an art form film in certain circles, sometimes affected but mostly original, a kind of antidote to Cinemascope, Doris Day and Hollywood spectacles, not to mention the looming wasteland threat of television.

Include French director Alain Resnais, who died at the age of 91, in that stellar group. Perhaps outside of Antonini, whose subject was a kind of ennui, he was one of the most difficult artists working in film. His “Last Year at Marienbad” was a puzzling, beautiful black-and-white riff on time itself, as the lead actors, the mysteriously beautiful Delphine Seyrig and Giorgio Albertazzi continually run into each other, the man trying to suggest that they had met and loved before, to which the woman inevitably replied, “Yes,” “Perhaps,” “I’m not sure” and so on. It was a film where you could walk into it in the middle and not be any more or less confused.

“Hiroshima Mon Amour,” a film about guilt and loss and living in modern times was, if not accessible, at least resonant, while his most dramatic—and least surrealistic—film was “La Guerre Est Finie” (“The War is Over”) in which the suave, tired Ives Montand played an old Spanish revolutionary with Ingrid Thulin as his lover.

Resnais—who once said that he “made difficult films but not on purpose” was part of the French New Wave triumvirate that included the radical, political Godard and the classic movie maker Truffaut (“Jules and Jim”) . They were as different as night and day, weekend and workday, clarity and Proust. Thoughts like that is why you went to those movies then. They made you vaguely excited, stimulated hitherto untouched places in your imagination.

Au revoir, Monsieur Resnais.

Kaplan: Biographer Whose Subjects Made for Great Novels

Justin Kaplan was one of the finest American novelist of the 20th century.

Trouble was he wrote biographies about great figures of the latter part of the 19th Century.

It wasn’t actually troublesome. Kaplan, who died at the age of 88 of complications from Parkinson’s Disease, believed that biography was an act of story-telling, that it was an art form, like a novel, like poems, and short stories and plays.

He acted on the belief in the works for which he’ll be remembered, biographies of Mark Twain, Walt Whitman and Lincoln Steffens, writers, who were very different as writers, men and iconic American figures.

Kaplan, although he was born the son of a man named Joe, who owned a shirt factory in Manhattan, was to the book born. His father loved literature, Kaplan himself got a degree in English from Harvard, worked as an editor at “Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations” and would later enlarge the great quote book considerably into the windy fields of the vernacular. He and married a novelist. With Kaplan, the word and the wordsmiths were kings.

His biographies were interpretative, to be sure, but also descriptive to the point of poetry: he loved lists, he would drag out words as if they were infantry and squads in the work entire, which was a division.

It wasn’t just that Kaplan wrote a form of literary work, it was that his construction of biographies tended to be unorthodox: not for him, he was born in, lived here and there, did this and that, and died time after at such and such a date.

For his biography of Mark Twain,which he called, significantly, “Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain”, and for which he won a Pulitzer Price, Kaplan began with Twain’s arrival in New York City after a colorful and raucous career on the Mississippi River and a humorist and reporter in California. It’s fair to say that he looked at the mansions of New York and saw a kind of serious future there, perhaps the man in the white suit, he was about to become.

But it’s not just Twain who plunges into New York. It’s Kaplan, too. Here is a lengthy description of New York worth quoting, because it says a lot about Kaplan and the environs where Twain found himself. “On Sundays, the upright and well-dressed, acceptable in the sight of both Lorenzo Delmonico and the Deity, went to services at Bishop Southgate’s or across the river at Henry Ward Beecher’s in Brooklyn, to be reassured that godliness and prosperity went hand in hand, mostly to see and be seen, the ladies patting their tiny hats which looked like jockey saddles and batter cakes.”

His concept was that Twain and Clemens were one and the same, a kind of self-created amalgam of characters. Other biographies of Twain have been written—including an interesting autobiography—but none was written better than Kaplan’s.

The same can be said of the Whitman biography, which begins when the great work of “Leaves of Grass” and the rest had already been written and Whitman moved into the role of great old poetic sage after moving out of his brother’s house where he had been living. He was 61 years old.

This becomes a process of looking back and into the mind of a true—if awkward, odd, outsider-American. In its range, the book is every bit as far-reaching as “Leaves” and Whitman’s work, generous, curious, celebratory, a biography of a true American original.

Kaplan’s biography of Lincoln Steffens, the great muckraking crusader and foe of the trusts and corporations, did not attract as much attention, because, in spite of being a writer, Steffens was not naturally so. He was a political man and champion of causes, not always prophetic, especially after his visit to the new Soviet Union and his comment: “I have seen the future.”