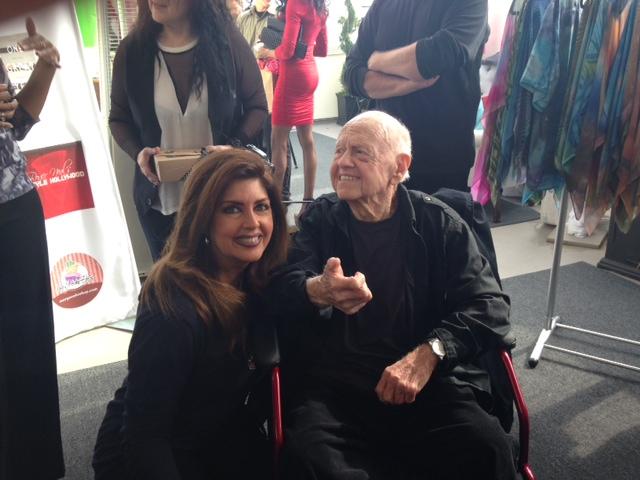

Hollywood Legend Mickey Rooney: No Small Life

By • April 11, 2014 0 889

Mickey Rooney has died. The first movie that Rooney, who was 93, ever appeared, he didn’t make a sound, didn’t say a word. That must have made him itch. The cause — or date — of his death was not immediately available, as it should be.

Not many actors of that era are left—the guys and gals who started out in vaudeville, their stage moms dragging them into the spotlight, their natural gifts finding the warmth of that light comforting and comfortable. Donald O’Connor, who will be always remembered for his “Be a Clown” in the movie, “Singing in the Rain,” recalled being put on stage by his mom when he was a toddler. That’s entertainment.

They would have started out in silent movies, the tail end of it, and that’s what Rooney, who still had some film and movies in the can, did, beginning a career that would last until: THE END.

For two years, the smallish—5-foot, 3-inches—Hollywood star, for that’s exactly what he was— was the top box office attraction in the world.

Not too shabby when you think there were people like Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, Cary Grant and Errol Flynn around at the top of their game. That was the time, when Rooney was making Andy Hardy movies, those series of movies which idealized small town America in a way that only MGM seemed to manage to do back then.

Rooney was a raffish kid, up to mischief if not no good, and he got fatherly advise from a judge played by Lionel Barrymore—the imposing leader of the Barrymore clan—and then Lewis Stone, who made a career of playing steady members of officialdom no matter what century—a bishop in Robin Hood’s time, a general during Pax Britannia and so on. He was also smitten by Judy Garland and Deanna Durbin, both budding teenaged stars at MGM, which, they said “had more stars than there are in heaven.”

He could sing—sort of—he could tap and dance, play the drums, clown around and be serious on the screen, even a little scary like the time he played a gangster in “The Last Mile,” which refers to that long walk to the electric chair experienced by many movie gangsters, including James Cagney. Spencer Tracy, in one of his priest guises, saved him from a life of petty crime in “Boys Town.”

For my money, one of the more interesting performances Rooney gave came as Puck in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” a black-and-white extravaganza from the 1930s, directed by Max Reinhardt, a legendary German stage director. Rooney’s Puck blazed around the screen like a derelict bee on drugs, eyes blazing, making his way through the Shakespearean lines almost like a latter-day rapper.

Rooney was a big star when the studios were big, and he took to stardom like water, although he did not take to adulthood as well. There were lots of child stars and grown-up stars around then, watched over by parents and agents and the studio bosses. By all accounts, Rooney needed lots of watching. He loved the track, and he loved the ladies. Quite a few loved him, at least for a while. His first (of eight) wives was quite a fetching catch by the name of Ava Gardner—the marriage lasted about a year. Others lasted longer or not.

Rooney continued to work—sometimes in memorable fashion as in roles in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” “The Bridges at Toko Ri” and a Playhouse 90 version of “Requiem for a Heavyweight.” Laurence Olivier—who ought to know—called him “the greatest actor of them all.” He had terrific energy. He could take a long and winding sentence and turn it into a punch line. He starred on Broadway in a musical revue called “Sugar Babies,” took to the road with his last wife in a show of reminiscences and even took a shot at “The Wizard of Oz,” the shadow of which his dear friend Judy Garland never quite escaped.

He cast quite a shadow, a big life fully lived, with few apologies.

Maybe now, somewhere over the rainbow, there’s this loud voice yelling: “I know. Let’s put on a show.”

For heaven’s sake.