Our First President Finally Gets His Library at Mount Vernon

By • October 10, 2013 0 1354

George Washington seems to many the inscrutable, difficult to know , the founding father built for a bust. Yet, at his home at Mount Vernon, Va., we have always come closer to him—he died here, he dined here, he worked his plantation and farm with diligence and care, living the life of love, family and mind after the wars and the heroic glories of being the first President of the United States of America.

We came closer still Sept. 27, when some 1,200 people, dignitaries, elected officials, trustees, intellectual worthies and members of the media gathered for the dedication of the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study George Washington at Mount Vernon. After more than 200 years, our founding father was finally getting a resplendent, next-to-his-home presidential library, thanks to the generosity of major donors and the untiring efforts of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.

David McCullough, the two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning American historian who has insisted and shown in all of his great works that history is about human beings, told a story about Gen. Washington at Trenton, N.J., In the last December days of 1776, as he rounded up his troops in formation and urged them to re-enlist for the princely sum of $10, which “was quite a bit of money in those days,” McCullough said. The general asked each man who was willing to re-enlist to step forward, “and then he started to trot away on his magnificent horse and turn around to see that not a single man had stepped forward.”

“Think of that moment when everything hung in the balance,” said McCullough, a spellbinder himself on a day when clouds ruled with occasional forays by sunlight. “So, he engaged the men again and appealed to something else.” The men, McCullough suggested, had above all an opportunity they would never have again anywhere else. This is what Washington said: “My brave fellows, you have done all I asked you to do, and more than can be reasonably expected, but your country is at stake, your wives, your houses and all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves out with fatigues and hardships, but we know not how to spare you. If you will consent to stay one month longer, you will render that service to the cause of liberty, and to your country, which you probably can never do under any other circumstances.”

“I can’t help but think,” McCullough continued, “that Washington might have inspired by Shakespeare’s and Henry V’s St. Crispin’s Day speech before the battle of Agincourt, appealing to his men, to them as “we few, we happy few, we band of brothers.” “I don’t know that, but Washington, as we shall see, was a reader, a lover of books, he was influenced by the Enlightenment, he liked the theater and Shakespeare and the classics, this has the ring of that.”

Listening to McCullough, our much-honored and perhaps most excellent historian in an age of excellent historians and biographers like Kearns, Isaacson, Meacham, Caro and Morris, to name a few, you could not help but feel you were present at a special moment in time, as if Washington himself, human and tall, would be greeting us at the door, once the door to the library opened in a moment of fanfare and confetti.

We were not far from his home, close enough to imagine the flowing river, the dock, the rooms and dining hall and landscaped gardens, and close enough to hear the hum of Americans from all over America—and other visitors from farther afield in the world as they traveled the world of George Washington. We watched and listened even as the city not far from here was encased in the embrace of dysfunctional partisanship and absence of manners of the kind which Washington abhorred and warned against.

The two senators—both Democrats—from Virginia were there, Mark Warner and Tim Kaine, both former governors, too, as is the pattern in Virginia politics, and hastened to say, after praising the spirit and the reality of the man, that they must hasten off to participate in the Senate vote on the funding legislation which had been produced by the House of Representative, complete with a proviso to defund Obamacare, all of which was looking like a prelude to a government shutdown come midnight Monday.

Such thoughts seemed almost unseemly at this moment because this was the home of the man whose every breath, word, cough, bow or not, pronouncement and act as the first President of the United States was precedent-setting, a fact the stolid, often stoic Washington was completely aware of.

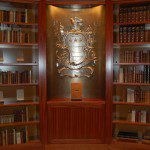

The library itself—centuries in the making but actually a matter of over two years in construction since the official groundbreaking in 2011—is a pleasing product, a tribute to the complicated man, his taste and an invitation, although we now know much about him, “to know more, we need to know more,” as McCullough said. It has the grandeur of old books, papers, volumes of writings, history made solid.

The completion and creation of the library was an unfulfilled wish on the part of Washington, as Mt. Vernon Regent Ann Bookout noted, quoting his own statement from 1797: “I have not houses to build, except one, which I must erect for the accommodation and security of my military, civil and private papers, which are voluminous and may be interesting.” They may indeed.

The library was created from funds of a capital campaign goal of more than $100 million for which the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, of which Fred W. Smith has been the long-time chairman, contributed a lead gift of $38 million. Other significant contributions came from the DeVos Family Foundation, John and Adrienne Mars, David M. Rubenstein and Karen Wright.

Virginia governor Bob McDonnell spoke, and the musical powerhouse couple of Amy Grant and Vince Gill sang, “American the Beautiful” and the dignitaries, including founding director Douglas Bradburn set off the official opening of the doors with a curtain drop and red-white-and-blue confetti flying. Everyone descended on the library, giving it a fullness and buzzy business it will likely not see again. Libraries—full of books of yore as well as new with scholarship and scholars—are, after all, known for silences occasionally interrupted by receptions and speeches.

Here, it was mingle time at this library, three floors, at once giving off a modern, cool and clean vibe attached to a warm, welcoming quality by the pitch-perfect design of MFM Design of Bethesda, Md., headed by MFM President Richard Molinaroli, who said that the design “should not look so contemporary that it feels disconnected. …This is a contemporary building rooted in traditional forms of architecture…When you walk into the building you should get an immediate sense of George Washington.”

This is immediately evident in the Karen Buchwald Wright reading room, where sun sprayed glass, offering a view of grass-green and tree-rich grounds, gold and brown colors, desks and comfortable chairs are presided over by Houdon-like busts of Washington and his contemporaries, an array of all-stars that include Jefferson, Franklin, Hamilton, Madison and Adams. “Washington was a great leader because he could move and inspire other leaders to work together, that they were in it together, “ McCullough said. Or as a man of the times noted, that if they failed, they would hang together.

In this environment, the mingling was easy—you could go into the reading room and run into former governor and former senator George Allen and his wife Susan or peruse the rare book room with former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and his wife Callista and chat briefly with them about the Wagner offering at the Washington National Opera.

You walk through the library among the old books—“Don Quixote,” the poets, “The Illiad” and realize that Washington was an eclectic man willing to pursue his thoughts as they struck him. “He loved the theater,” McCullough, who is working on a book about the Wright Brothers, told us. “He must have seen Addison’s ‘Cato,’ a popular play of the time about the last and fiercest defender of the Roman Republic,” a play which is rarely, if ever, performed these days. Washington read Alexander Pope who advised, “Act well the part, there all the honor lies.”

And there, and here, it lies still.

“I didn’t know Hamilton was so handsome,” a woman was heard saying in the reading room, as she looked up at the busts looking at each other.

You imagine them some night, moonlit, when only guards remain somewhere in the building, imagine them having silent conversation, this band of founding brothers, breathing thoughts and memories here at the library.

- Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., speaks at the opening. | Robert Devaney

- Nora Birch