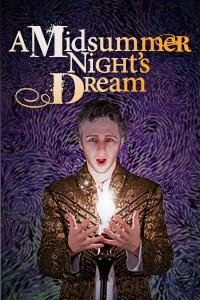

The Mythopoetic Show Business of ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’

By • December 3, 2012 0 1044

When actor Ted Van Griethuysen, as Quince, the leader of the rude mechanicals gathered in the forest for a rehearsal of “Pyramus and Thisbe,” makes his entrance, he appears quietly, almost furtively, and he starts to sing, slyly, but happily, not loudly:

“There’s no business like show business. There’s no business I know …”

It’s a little thing, a kind of reminder that this play is—among the many things it is—a paean to theater and, yes, to show business, a theme that Shakespeare being a man of the theater in his times and the man of theater in ours, addresses many times in his plays. It doesn’t stop there either: as the mechanicals torture their way through their rehearsals and encounter many a problem, Quince reassures himself with selections from “The King and I” and “The Sound of Music.”

The show tunes are one of many conceits with which director Ethan McSweeny flavors this production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”—that the theater, with its traditions and magic, is one of the characters in the production. It’s a place where imagination comes to believable life in the form of fanciful fairies—albeit some dressed in the school of fashion accompanied by bustiers and garter belts—grand entrances, tragic-comedies told by heartfelt fools, rulers just a step removed from fable and legend, and a quartet of lovers pixilated to the point of total humiliation by an otherworldly being named Puck.

This production, which appears to be set in either somewhere north of the 1930s and south of the 1950s, in England or America or both, but always in Athens and a magical forest, is full of entrances meant to signify. Oberon, the king of the Fairies, makes his first appearance like a rock star in a cape, like Roger Daltrey in front of a white screen. Theseus and his bride-to-be Hyppolyta, the Queen of the Amazons, he in military head of state form, she as formal-dressed stunner, appear before gathered paparazzi, the fairies make their first appearances slowly, preceded by points of light from openings on the stage as if by: magic. Those same openings later become traps to fall in, trampolines to appear flying as if part of an abbreviated tumbling act.

In this production, the stage, like everyone else—or as Quince tells Bottom after he appears with the head of an ass—is “translated,” as well as always transformed.

What the production really seems to remind you of is a circus, a carnival, a sideshow, and bits of the most excessive parts of operas that don’t involve music. It’s theater and show business in all of its guises. It is, too, a dream we can swim in.

“Midsummer,” of course, has several balls up in the air. There’s the wedding of the rulers, and their sometimes not settled love. There’s the two couples Lysander-Hermia and Demetrios-Helen. Hermia loves Lysander, but is all but betrothed to Demetrios and Helena is smitten beyond reason with Demetrios who loves her not. There is Oberon, his queen Titania (ill met by moonlight), battling like a divorced couple over custody of a changeling boy. There is Puck, the frisky spirit of the night and Oberon’s hench boy, who, with some sprinkling of exotic fairie dust wreaks havoc with the lovers, makes Titania fall in love with the head-of-an-ass Bottom.

Finally, there are the rude mechanicals who have fallen in love with theater and the play they are to perform. They are worth mentioning because they are the salt of the earth and members in good standing of the 47 percent, a carpenter, a weaver, a bellows-mender, a tinker, a joiner, a tailor. They are, each and every one of them, transformed into thespians doing “Pyramus and Thisbes,” a tragedy faintly echoing “Romeo and Juliet,” but pure sweet, ineffectual nonsense in the hands of these our players. None is more the thespian than Nick Bottom, played with such honest hyperbole—Bottom’s middle name—that the word ham only begins to tell the tale. He wants to and thinks he should play all the parts. He survives the shock of his vivid dream as the lover of a queen with refreshing malapropism that sound like the truth. Bruce Dow does what Nathan Lane might try to do with the part, if only he could. His squeals, sighs and wild dog eagerness are a comic delight in a show which has many.

In dealing with the lovers, McSweeny resorts to the kind of physical comedy in which the characters suffer gross indignity—from losing much of their clothes to slipping, falling and sliding on a slippery stage. The players all bring it off with superb timing: Robert Beitzel as a kind of garage rock Lysander, Amelia Pedlow as the self-assured Hermia, Chris Myers as the smug Demetrius, and best of all, Christiana Clark, who, after enduring yet another humiliation, brings the house down with a grandiosely exasperated “Oh, excellence!”

If Tim Campbell and Sara Topham are the dream catchers and creators as the rulers—both earthly and fairyland—it is Puck who is modern mischief incarnated. He is the joker in the deck, the prospect of chaos, the knowing fool moving faster than the speed of hummingbirds, but he’s also the caretaker of his dream world and our dreams.

Puck suggests to us that “we have but slumbered here, while these visions did appear.” Fat chance of that. This “Midsummer” may feel like a dream, but it’s a vivid dream we won’t soon forget.

Shakespeare Theatre Company’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” runs through Dec. 30 at Sidney Harman Hall, 610 F St., NW; 202-547-1122 — ShakespeareTheatre.org.