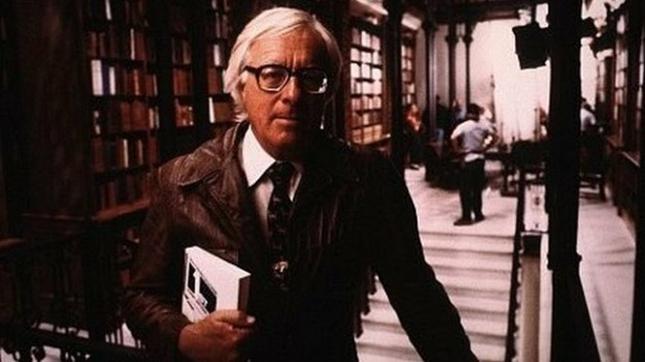

Ray Bradbury, Our Forever Writer of Dreams Come True

By • August 10, 2012 0 1468

A 91-year-old writer of fantasy, science fiction and horror stories and books died this week, and everyone stood up and notice. Ray Bradbury disdained the internet, cellphones, even though in one way or another, his works of fiction had predicted just about every modern technological miracle we have. He was a self-described dreamer.

In his passing, it was as if a whole world of fans and like-minded dreamers suddenly woke up from a dream of not remembering him and their voices were heard all over the world—from President Barack Obama and movie producer-director Steven Spielberg to perhaps the most prolific author of fantasy and horror novels Stephen King. All of them sang sad songs of praise. He was a giant in our midst who did not roar but accumulated memories of the future and fond recollections of the past for us all of his life.

On that same internet, the bloggers and insipient, if not insipid, comment makers buzzed with his name. While my search was not thorough, I’d bet few individuals had anything bad to say about him. Snarks, of course, are out there somewhere, but who cares.

I read Bradbury’s short stories when I was in high school when I lived in a small town in Ohio that was equal parts of his “Dandelion Wine” and “Something Wicked This Way Comes.” Bradbury’s writings—short stories, movie scripts, novels, essays, and scribbling beyond category —endure, and his death reminds us of how well placed and hidden they were in our psyches and communal literary, bookish memory.

My friend recently used “Fahrenheit 451” as a teaching tool for her middle school ESL students, and surprisingly, got a burst of interests from students from Ethiopia, El Salvador, Nigeria and Asia that proved Bradbury a true prophet. He was born in 1920 and lived a life that saw so many changes—many of which he foresaw in his stories—it would make most people dizzy with the recklessness of the results.

He wrote “The Martian Chronicles,” a strung-together group of tales about the last civilizations on Mars. It did not involve John Carter, although, predictably, Bradbury loved Edgar Rice Burroughs. He wrote the aforementioned “Fahrenheit 451,” which envisioned a society where firefighters, instead of putting out fires, started them to burn books and book collections. This was made into a fine, if critically mixed, film directed by Frenchman Francois Truffaut, starring Oscar Werner and Julie Christie, and left us with the indelible image of men and women turning themselves into living books, committing the great works of literature to memory in a forest where it seems it’s always snowing.

Bradbury was characterized as a science fiction writer. In truth, he saw himself as — and was— a writer of fantasy stories. In point of further fact, he was much better than that: he was a writer of great and lasting literature, by my way of thinking, who just happened never to have won a Nobel Prize for Literature. He committed the sin of being both popular and unforgettable. Imagine such an outpouring of comments and feeling of loss as well as a need to celebrate after the passing of the great Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, one of the less obscure Nobel literature prize winners.

In front of me, I have an old book, “The Stories of Ray Bradbury,” in which the man himself wrote a lengthy introduction called “Drunk and in Charge of a Bicycle.” The collection is by no means complete, but it has almost all of the highlights— 840 pages worth —including “The Night,” which begins thus: “You are a child in a small town. You are, to be exact, eight years old and it is growing late at night.” The book ends with “The End of the Beginning,” an apocalyptic tale that ends thus:

“He moved the lawn mower. The grass showering up fell softly around him; he relished and savored it and felt that he was all mankind bathing at last in the fresh waters of the fountain of youth.

“Thus bathed he remembered the song again about the wheels and the faith and the grace of God being way up there in the middle of the sky where that single star, among a million motionless stars, dared to move and keep on moving.

“Then he finished cutting the grass.”

If you suspect touches of Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe—the elder, so to speak—or Dickens in this, you would be right. One of the joys of Bradbury is the joys he had in books and writers. He was not competitive, but generous and would weave Wolfe, for instance, into a story about the writer who should be on a space flight to Mars because he came so close to getting every single thing into his novels, or how a group of wealthy Hemingway fans got together and built a time machine, which would allow Hemingway to die a Hemingway death, instead of that horrifying suicide by shotgun.

Bradbury appeared to have loved the Irish because he wrote funny, out-loud-laughing stories about them, none more so than “The Terrible Conflagration up at the Place”. He wrote the screenplay for the John Huston-directed movie version of “Moby Dick,” which had the unlikely castings of Gregory Peck as Ahab and Orson Welles as Father Marple. He wrote “I Sing the Body Electric.”

He wrote futuristic books that predicted well because he understood the past—and he envisioned a horrifying T-Rex long before Michael Crichton did. He was born in Waukegan, Illinois, which resonates Midwest summer like fireflies. He predicted automatic teller machines (ATMs) and ended up hating them when they materialized, not from his mind, but at a bank. His tales, novels and stories turned up on movie screens, on television, and on the dreaded internet. He was and remains everywhere. The credit line: 27 novels, 600 short stories, eight million copies of his works in print and all over the . . . internet.

Bradbury said: “I don’t believe in colleges and universities. I believe in libraries. And of course: books. Word.

In 1932, still a kid of sorts, he went to a carnival and met a carny entertainer named Mr. Electrico who touched him with an electrified sword and told him “Live Forever!” At that point, Bradbury became a writer—and a magician, which he wanted to be. Bradbury is, of course, both writer and magician. I found this on the internet.

“Live Forever!” And he did, and he has and he is.