Anna Deavere Smith Does Not “Let Down”

By • July 26, 2011 0 1192

At the end of “Let Me Down Easy,” Anna Deavere Smith’s provocative, shattering play about health care in America now and the hour of our death, Smith stands alone on a stage littered with castoff costumes, clothing, food, props, bottles, pencils, lying on the floor. It looks like the aftermath of a party or a food fight—or an abandoned emergency room where a life-and-death struggle has just taken place.

It’s all that remains of the 20 people portrayed by Smith during the course of an uninterrupted and rangy evening in which she explores, in her inimitable fashion, the arena of our health and bodies, and the pains we sometimes endure because of the way we deal with falling ill, and the moment when we come face to face with the finality of death. By a shift in vocal timbre, a way of walking or sitting, an accent, a laugh, a sprawl on a couch, a way of talking, outstretched arms, a tie, a coat, a cowboy hat, she explores and portrays the geography of our culture.

Smith, an impressively talented, cogent and curious, woman functions as playwright, actress, writer and interviewer for “Let Me Down Easy,” a project somewhat similar to others she is well know for. There was “Fires in the Mirror,” which examined the aftermath of a race riot in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and “Twilight: Los Angeles,” which focused on the devastating and violent 1992 riots in Los Angeles. But while these previous works also saw Smith portraying dozens of real people alone on stage with remarkable dexterity and even-handedness, they were focused on specific, dramatic and explosive events. “Let Me Down Easy” is much broader in its scope and approach.

While the massive national health care reform legislation, passed amid much bitterness last year, provides a framework for a large extent of what concerns the people in this play, there is a lot more going on than might be contained in even such a sweeping legislative effort.

“Let Me Down Easy” is about specific people, many of them quite well known to most of us for one reason or another. Athletes, like the controversial American Tour de France bicyclist Lance Armstrong, who overcame cancer and rode to greater achievements. Sportswriter Sally Jenkins. A boxer. A rodeo bull rider. Model Lauren Hutton. Television movie critic Joel Siegel, dying on a couch of colon cancer. Playwright and performer Eve Ensler, of “The Vagina Monologues.” Former Texas Governor Ann Richards. There are doctors, medical academics, a musicologist, a choreographer and a physician at Charity Hospital in New Orleans who experiences the terrifying ravages of Hurricane Katrina.

Such a diverse group of voices, of men and women from various walks of life expressing similar and differing concerns, at first produces an unformed, disconcerting narrative, like trying to grab Jell-O with your hands. But the effect, in time, is accumulative, and it arrives with shocking and powerful clarity, and with gentle but undeniable finality. It may not be a definitive destination, an over-arching theory or philosophy, or even ready-made solace, but it is a destination, an arrival, and an ending.

There have been complaints that there are too many celebrities here and that the play is unfocused or mish-mish. Maybe so. Maybe it’s too big a subject to have a definitive story line or conclusion that you can take to the bank or to the church. And it’s fair to say that the better-known people portrayed here add less to the total than those not so well known. While much of “Let Me Down Easy”—a theatrical blues riff with multiple meanings—concerns itself with terminal illnesses and how it is dealt with by hospitals, the medical community and patients, there are sections on the ailments and issues peculiar to athletes, as well as how society deals with women’s bodies and their functions (hence Ensler and Hutton).

But many of the characters share a common plight against cancer, a battle, sometimes successful, sometimes not. And suddenly there is very little distance between women like Richards, the sharp-tongued former governor of Texas dying of cancer, and Smith’s own aunt, Lorraine Coleman, a retired teacher.

There is a surprising bit of laughter in the play—some as a result of Smith’s fabulous work as a mimic, mime and master of comic timing—but the constructed and performed production picks up power as it goes along. A kind of dread aching to be relieved ensues somewhere in there. Smith gives us Kiersta Kurz-Burke, a physician at the New Orleans charity hospital who has been ignored and abandoned for days during Katrina; Eduardo Bruera, of the Anderson Cancer Center, talking about “Existential Sadness”; Joel Siegel, only in his fifties, flat on his back, the face projected dramatically on a wall, dying of colon cancer; and Trudy Howell, the director of a South African orphanage where children deal with the loss of parents and their own impending deaths, entitled appropriately, “Don’t Leave Them In The Dark.”

“Let Me Down Easy” has a restless feel to it, but it also has the sure touch and magic of Smith’s abilities as an actress, that gift of playing many parts convincingly with minimal props. Over and above the identifying tricks of such props, or the brilliant use of her voice and inflections of accents, tone and vocal speed, there is something else that convinces us like a punch to the heart. True, Smith is a terrific actress—you’ve all seen her in films and as a national security adviser on the defunct “West Wing” series—but that’s technique. What makes her work soar is her own empathy toward the people she’s put on stage; it’s as if she’s caught souls in a glass jar. She’s not a chameleon. Some recognizable part of her is always there. It’s not as if she somehow disappears into a person. It’s more like she joins with them.

“Let Me Down Easy” doesn’t function so much as drama; rather the people that we come to know as they swagger, suffer, snack, snort, laugh and dream are a kind of self-portrait of us. What we often hear are sentences we’ve heard, or what we will ultimately say ourselves sooner or later.

We’re left with a salve, like fresh water, And Smith stands alone in a bow, the stage littered with the debris, the left behind stuff of human beings.

“Let Me Down Easy,” written and performed by Anna Deavere Smith and directed by Leonard Foglia, will be performed at Arena Stage through February 13. For more information visit ArenaStage.org.

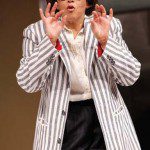

- Anna Deavere Smith in “Let Me Down Easy” at Arena Stage | Courtesy of Arena Stage