The Taste of Conservation: Cleo’s Dinner Table Revolution

By • July 26, 2011 0 1900

Walking around Cleo Braver’s backyard, looking out onto the Goldsborough Creek as hundreds of geese acclimated to their winter stead, it was easy to get lost in the crisp afternoon warmth. The East Coast and Bay area is a place of surprising beauty, even to those of us who have lived here all our lives. But it takes a certain kind of person to grow something out of that beauty. Leaving your job to start your own organic farm and promote Bay awareness and safe farming practices may not seem to be the most practical decision for most people, but for Braver, it was the only option.

Originally an environmental lawyer, Braver and her husband bought Cottingham Farm, a 156-acre property resting on a tributary of the Chesapeake Bay, for but the joys of living on such a property. Like the majority of farmland in the area, her land was tenant farmed. “It’s an owner like me who goes to her job during the day, and there’s a farmer, called the operator, who comes in and works the farm. You’re sharing the cost and you’re sharing the benefit, but you’re not really getting involved in it.”

Also like most farmland in the area, her 90 acres of tillable fields exclusively grew corn and soy for animal feed, notably for chickens in the industrial farmlands on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. “We were a quintessential post-World War II farm,” she said, with more than a hint of cynicism.

Having been an environmental lawyer, and her husband a serial environmental entrepreneur

currently involved in the water and wastewater treatment business, the nature of agricultural

wasn’t alien to Braver, but as she said, “We were just living here. But we weren’t involved in what’s going on with the farm. We were living on the land, we were enjoying the land. We used it a lot, but we didn’t run the fields. We had no understanding of farming because we’re not farmers.”

However, as a lawyer is prone to do, Braver began to read up on farming, modern nutrition and the environment. Slowly, over five years, she digested information about the impact of industrial farming practices on the Chesapeake Bay and its effects on topsoil, animal health, human health, and the economy. “There is so much information available if you seek it out,” she said, rattling off a slew of books and information centers, among them Michael Pollan’s “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” and John Robbins’ “Food Revolution.”

She grew greatly passionate for the state of the environment and the health of her community, and decided to take matters into her own hands by converting her farmland to an eco-friendly, organic farming operation. Initially, her mission was purely environmental, not humanitarian.

The first step she implemented was the addition of buffer strips around the perimeter of the property to protect the water. A buffer strip is a 100-foot wide strip of land surrounding the farming fields that uses deeply rooted, perennial, warm season grasses to help control soil and water quality, trapping sediment and enhancing filtration of nutrients and pesticides by slowing down and absorbing runoff that would otherwise enter local surface and ground waters. There is additionally a 120-foot wide native tree and shrub riparian buffer on the edge of the Creek, which is comprised of thousands of native trees and shrubs. Her farmer at the time did not want to do it, as it took away from tillable land. So Braver decided to take control of the farm on her own. “You may think they’re meaningless, these little buffer strips. But a 100-foot buffer strip, along the outside of the fields, adds up.” It ended up being 30 of the 90 acres.

The next thing she did was convert a hydric or wet field to a 20 acre shallow wetland. All these installations were done with the help of Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage, a local nonprofit organization which installs grasslands, wetlands, woodlands and other habitat in Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Each year, she discovered, five tons per acre of sediment, and 10 pounds of phosphorus and 100 pounds of nitrogen would be carried off the land into the water, causing dead zones in the water where no life can be supported. She found subtle but important signs that something was amiss below the surface: Fish attempting to aerate the water between dusk and dawn, when dissolved oxygen levels are lowest; disappearing submerged aquatic vegetation; and the disappearance of all but the last one or two percent of historic oyster populations in the Chesapeake. After Braver put in the buffers, there was no sediment-laden rainwater leaving the farm, a sign that things were moving in the right direction.

Another big piece of the puzzle was the utilization of cover crops. A cover crop, such as winter wheat or rye, is planted in the fall, and it stays in until spring. Its job is to hold the soil together when it needs it the most; when the winter winds and tremendous precipitation is scouring the land. “The whole point,” says Braver, “is you’re not making the land work yet another crop that year. You’re trying to rejuvenate the soil with a high nitrogen crop, and then you till it in. That’s how you build and till the soil. Not by using synthetic fertilizers in the springtime.”

Acting quickly (almost precipitously, as she’ll tell you), Braver decided that what Maryland needs is a new green industry that grows real food containing no pesticides or herbicides. The food would be grown by locals and purchased by locals to take the place of food grown by California, Florida, Canada and Mexico. On top of the health benefits, the jobs it would create and the revenue it would keep within the area, this plan would cut down on the global warming and other impacts of food, which travels an average of 1500 miles to get to our plates.

While this may not seem practical, organic farming as she explains it does much more with much less. An acre of organic farmland can easily employ four workers, and produces far more fruit and far less waste than an acre of non-organic farmland. “I was growing heirloom tomatoes (bred for nutrition and taste rather than for transportability, uniformity and shelf life) for local restaurants and for an Annapolis and Baltimore Whole Foods on an acre of land,” she said. “That’s all. What it takes is people. I had seven people working with me working on a little less than two acres.

“This kind of agriculture does not take up a lot of land. It can be done anywhere. It can be done in the city. It is being done in the city. It’s fallacious to say we can’t feed the country on our land. What this movement needs now is the infrastructure to support it. We need to build a local sustainable food integration facility where sustainable or organically raised vegetables, meats, fruits and dairy can be processed, packaged, sold and distributed within a hundred or so mile radius, and where families can learn cooking, nutrition and wellness, and come together around food five days a week year round. This is as necessary to us today as the highway infrastructure of the 1950’s.”

She wanted to learn firsthand some of the production, marketing and distribution issues. Until early 2009, her sole foray had been to grow heirloom tomatoes for a local farmer’s market in Easton. “I considered it a grand success since my tomatoes were photographed by two food stylists and then were invited to a wedding.” she said.

In a few week period in January and February of 2009, Braver attended an intensive conference on sustainable farming and purchased two 96-foot long high tunnels, or plastic greenhouses, to build on Cottingham Farm. On June 9 of that year, she had made her first delivery to Whole Foods.

“My mission started out as being strictly environmental,” said Braver. “But what I’ve learned over the course of doing this for the last 18 months has blown my socks off. The health care issues are just as big, if not bigger.” For instance, she sites the difference between eating a free-range chicken egg and a CAFO chicken egg (industry abbreviation for Confined Animal Feeding Operations). A CAFO chicken is fed almost exclusively corn and grow under such harsh conditions that they require regular non-therapeutic doses of antibiotics to survive.

A free-range chicken egg has high levels of the “good cholesterol”, vitamin D and Tocopherols, because the chicken has been able to roam around outside. A CAFO egg has less of the good and high levels of the bad cholesterol. Needless to say, Braver plans to put up a chicken coop in the spring, as well as raise heritage turkeys, ducks and geese.

Her mission has become an education agenda— one to inform landowners and the public about playing a role in the change from industrial agriculture to a food supply system where food is produced sustainably and distributed locally.

“Most families don’t know that corn-fed red meat has seven times the level of saturated fats as the meat from a pastured animal. But the eating public can change the industry and their lives, by voting with their forks.”

However, the lack of knowledge stems deep. The vast majority of American physicians, she explains, no longer receive nutrition training in school. “And the American family doesn’t get it,” she said. “I didn’t know that if you apply pesticides to a vegetable it stops producing antioxidants, and that you can lose six pounds a year just by switching to grass fed meat.”

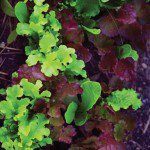

Braver’s farm now grows a vast assortment of seasonal produce. Her current offerings include a peppery Arugula, Mizuna, Tatsoi and other Asian greens, red, green, orange, yellow and silver Butter Chard, green, red and blue Kale, Spinach and Collards, three colors of Beets, red, yellow and orange Sweet Carrots, and other offerings like French and Asian Heirloom Winter Squashes and radicchio, dandelion and chicory. She grows this all on about two acres.

She distributes to seven restaurants, including the Bartlett Pear and the Out of the Fire (where her produce is highlighted on the menu), as well as Whole Foods and two local markets. If visiting Easton, her produce can be purchased year round at the European style Market House at Easton Market Square (open Thursday through Sunday).

Braver’s first step was becoming a food producer and learning the markets, and in the process she learned how tremendous the demand is for healthy food, including within hospitals, schools and prisons.

The next step is to help this industry grow. “I want to build a facility with the help of policy makers in a visible place where food gets integrated. So whatever landowner wants to sustainably grow food, whether it’s meat, dairy, vegetables, we would try to create an infrastructure to help people do that on their own property, even providing the staff to do it. And then it gets integrated into this food production facility, where the produce gets washed and packaged, so there’s a retail facility, where people know they can go buy food that is healthy and clean. There’s a distribution facility distributing within a hundred miles—a sustainable food chain. There will be cooking classes, wellness classes, nutrition classes…”

As she rambled on, brimming with excitement and filled with conviction and industry knowledge, it became clear that this farmer is more than an idea woman. She has her money where her mouth is—and I don’t mean that proverbially. This project, like her others up to this point, will reach fruition. The cost and hardships are of no concern to her, for the toll it takes is negligible when compared to the cause for which she is fighting: the health and wellbeing of her community at large. “The cost of industrial agriculture is not included in the cost of food,” she warned, “but be sure that we pay it in the end.”

- Jordan Wright

- Jen Merino

- Photo by Aaro Keipi |www.aarography.com

- Photo by Zachariah Weaver

- Robert Devaney

- Inside the greenhouse | Yvonne Taylor