Man’s Best Friend, Through the Ages

By • July 26, 2011 0 1559

If you asked most people what Middleburg, VA has that can’t be found anywhere in the U.S., you’d probably hear something sounding a little like a travel brochure.

Something like: a thriving equestrian culture just an hour outside the city, a chummy community of tavern owners, vintners, billionaires, and shopkeeps, a tradition of rustic living held onto as tightly as horse reins.

What you probably won’t hear about is the nearby, near-priceless cache of books in the National Sporting Library and Museum’s basement.

But you should. The library’s trove of rare books and art, everything from first editions of Hemingway and Walton’s “Compleat Angler” to the paintings of sporting artist Alfred Munnings to Paul Mellon’s collection of antique weathervanes, gives you that surreal, ghostly feeling you get around something beyond your age and time. Embrace it. The 56-year-old library’s holdings are the envy of scholars across the Old and New Worlds, and in the esoteric worlds of classical sportsmanship — that is, angling, foxhunting and the rest — the collection there reigns supreme. And just in time for summer’s proverbial dog days comes the library’s newest exhibit, “Lives of Dogs in Literature, Art and Ephemera,” a one-room shrine to man and, more importantly, man’s best friend.

“We decided to focus this on the complex relationship between humans and dogs and show, over 400 years, some of the examples of how people related to their animals,” said Mickey Gustafson, the library’s communications director and curator of the exhibit. The inspiration came from a lecture at a library symposium last fall by gallerist William Secord, whose book on the dog’s historical role in art caused such a stir it prompted staffers to dive into the archives looking for more artifacts to make into an exhibit. They soon found their cup running over.

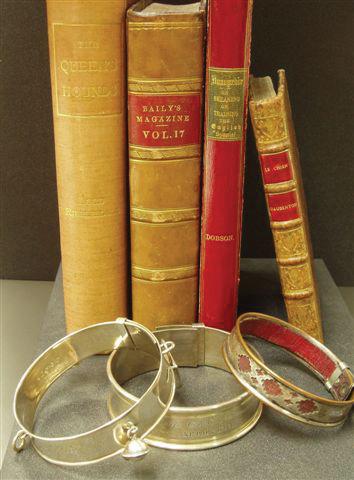

“It was culling, narrowing down,” Gustafson says. “We had over 75 [dog] collars, for example, and you’ve seen how many books we have. Within the books, choosing what page to have open, and finding relationships between all these things … That’s fun. To me, it was like creating an installation, like an artist, almost.”

Actually, it would be hard to deny any claim to artistry or history, especially since the exhibit — and museum — are practically alive with it.

Founded by sporting enthusiasts George Ohrstrom and Alexander Mackay-Smith in 1954, the collection that started with 7,000 assorted volumes has grown to 17,000 meticulously categorized titles, some dating back to the 16th century. The library is open to the public, who may freely browse most stacks, but may not check out items.

The main floor, appointed in wood boiserie, is stocked with books on everything from bullfighting to fly fishing, but it’s the rare book room on the bottom level, temperature controlled and sealed behind glass, that should get the bibliophile’s juices flowing (tours are available by appointment Tuesday through Friday).

“This is really unique material, and a lot of this has never seen the light of day. There’s lots of that kind of stuff here that people just aren’t aware of,” said the library’s Chief Operating Officer Rick Stoutamyer, born and raised a sportsman in West Virginia before entering the rare book business.

Besides a healthy collection of first editions throughout, the rare book section houses the library’s oldest volume (on dueling, dating to the 1520s), along with an original manuscript penned by a young Theodore Roosevelt, in which he wrote about Long Island fox hunting for the now-defunct Century Illustrated magazine. “The thing that’s really cool about it,” said Stoutamyer, “is if you look there’s very few corrections, really. He pretty much knew what he was going to say when he sat down to write it.”

Not bad for a budding president. Elsewhere, readers can find an original set of John Audubon’s “Birds of America,” the riding tutorials of Vladimir Littauer — who brought to America the idea that riders ought to lean forward on horseback — and a beautiful collection of fore-edge paintings, jargon for watercolors painted over the edges of a book’s pages.

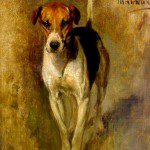

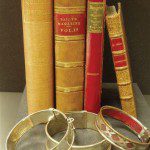

Inside “Lives of Dogs,” entrants are greeted by a bronze bust of a foxhound, its expression etched somewhere between curiosity, drive and affection. It forms the center case in a square room, surrounded by other boxes of glass tucked against the walls. Within each sits an antique dog collar or two, some picked for their craftsmanship, others for quirks. One collar, built for hunting, sports a row of sharpened metal teeth to protect the hound during a scrape with pugnacious wildlife. Another, daintily built of sterling, bears the Tiffany’s stamp and, not surprisingly, a Gramercy Park address.

Throughout the cases are books of sketches and paintings and scenes of the hunt, the infectious excitement and pandemonium enough to move even 21st-century eyes. One engraving by the Belgian Johannes Stradanus, for instance, shows a royal hunt reaching crescendo: the lord holds his spear aloft, his hounds nipping at the stag’s heel. In his “Booke on Hunting” Englishman George Turbervile extols the culture of the hunt, well over a decade before Shakespeare even lifted a pen.

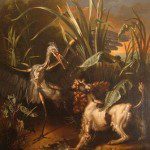

And on the walls you have the paintings, including Oudry’s “Poodle Flushing a Heron,” displaying the flourish that made him a favorite of Louis XV. “The king of France became really fascinated by [Oudry],” says Gustafson. “He would invite him to the palace and have him paint portraits of his dogs while the king watched and talked to him. He was immensely successful. In the development of European art, there’s this sense of eventually becoming interested in depicting things realistically and then also with a lot of drama and decoration. Things are not as easily defined as we often think.”

You could say that again. In the painting, a poodle has cornered a large heron, reared up in a fashion starkly frightening and primal, a kind of rage at wit’s end. On the adjacent wall hang a few (gentler) landscape works by John Emms — pastoral, faintly sentimental and, of course, crowded with dogs.

As a whole, the exhibit serves to remind us of the animal that touches and shapes our lives, sometimes as much as people do. Since it opened in late May, it has proven a hit, not least among dog lovers. “I think it’s really a rich environment, and we’ve had a lot of people who come to see it, and they seem to spend quite a bit of time here,” says Gustafson. “A woman was here the night we opened and she really knew dogs and [pointing to a painting] instantly said, ‘That’s a French dog, a French beagle.’ … Some other people came in and talked about the collars. Different things were appealing to different people.”

“Lives of Dogs” is on display until Dec. 11 at the National Sporting Library, 102 The Plains Road, Middleburg, VA. Admission is free.

This article appeared, in condensed form, in the Aug. 11 issue of The Georgetowner.

- Nineteenth-century sterling silver dog collars. | Courtesy National Sporting Library & Museum